Precis

Biotic and abiotic factors are progressively given to synergistically shape broad-scale species distributions. Nevertheless, the relative importance of biotic and abiotic factors in predicting species distributions is unclear. In particular, biotic factors, so much as predation and vegetation, including those ensuant from anthropogenic shoot down-use deepen, are underrepresented in species distribution modeling, but could amend sit predictions. Using general linear models and simulate selection techniques, we used 129 estimates of population denseness of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) from 5 continents to evaluate the relative importance, magnitude, and direction of organic phenomenon and abiotic factors in predicting population density of an invading bigger mammalian with a global distribution. Incorporating diverse biotic factors, including agriculture, vegetation cover, and large carnivore affluence, into species distribution modeling substantially improved model fit and predictions. Abiotic factors, including haste and potential evapotranspiration, were also Copernican predictors. The predictive map of population density revealed fanlike-ranging potential for an invasive large mammal to expand its dispersion globally. This entropy can cost utilised to proactively produce conservation/direction plans to control future invasions. Our canvas demonstrates that the on-going paradigm shift, which recognizes that both biotic and abiotic factors bod species distributions across broad scales, can be high-tech aside incorporating diverse organic phenomenon factors.

Introduction

Predicting and mapping species distributions, including true range and variance in abundance, is fundamental to the preservation and direction of biodiversity and landscapes1. The ecological niche defines species-habitat relationships2,3,4 and provides a useful framework for understanding the compass and copiousness of species in relation to organic phenomenon and abiotic factors. Further, niche relationships across local scales can supply novel information astir the ecology, conservation, and management of species at macro scales5. Most studies evaluating a species' ecological niche across their dispersion focus on front-absence occurrence data to predict the geographic range6; however, preservation and management plans for species can be improved past sympathy patterns of population abundance and compactness across a species' range7. In particular, evaluating population density, compared to occurrence, can reveal novel patterns of species distributions in relation to landscape factors8.

There is an ongoing image change over in apprehension how biotic and abiotic factors shape species distributions. Until late, it was widely accepted that abiotic factors, such As temperature and precipitation, played the primary role in defining distributions of species and biodiversity at broad scales (e.g., regional, continental, spheric extents) and that biotic factors were most measurable at fine scales (e.g., locate, local extents)9,10,11. It is increasingly recognized, however, that organic phenomenon factors are important determinants of species distributions at broad spatial scales, especially when considering biotic interactions12,13,14,15,16. Although interspecific competition can be an strategic biotic determinant in species distribution models at broad scales, other forms of biotic interactions, such as predation and symbioses, lav also represent important determinants15,17, merely have standard less aid18. In addition, although researchers have evaluated the personal effects of organic phenomenon interactions on geographic range limits18, relatively a couple of studies sustain evaluated how biotic factors influence population density across a species' range19,20, which can be more informative in understanding macro-ecological patterns7,21.

In addition to species interactions, biotic factors related to vegetation buns tempt species distributions and abundance at broad scales. In detail, anthropogenic land-employment change is rarely considered when evaluating species distributions at broad scales; however, given the human footprint globally22 and projections for expanding hominid impacts on the environment23,24, biotic factors created away human activities are potentially chief predictors that stern contribute to a better agreement of species distributions8. For deterrent example, rural crops are a sovereign organic phenomenon factor across continents that are facilitated by human engineering and the redistribution of ecological resources and energy, which can have profound impacts on plant and animallike populations across broad extents; agriculture can increment populations for some species through increased food, resource availability, and landscape heterogeneousness, or decrease populations due to passing of home ground25,26,27. Ultimately, further evaluation is necessary to understand the relative importance of abiotic and biotic factors in formative species distributions crosswise broad spatial scales13,15.

Invasive species are a primary driver of far-flung and severe negative impacts to ecosystems, agriculture, and humans across topical to global scales28. These introduced plants and animals often exhibit broad earth science distributions, can be relatively well studied across local scales, and provide new opportunities to evaluate broad-scale patterns of niche relationships29. Predictions of potential geographic distribution of invasive species can provide critical information that can inform the prevention, eradication, and control of populations, which has been evaluated for many taxa, including plants30, amphibians31, and invertebrates32. However, few studies have predicted the potential ranges and teemingness of non-domestic mammals33. Especially for wide-ranging species that give the axe pass crossways broad extents of landscapes, predictions of how population density varies spatially can provide important information for prioritizing preservation and management actions.

Few species exhibit a globular statistical distribution that extends across Europe, Asia, Africa, Northeasterly and South United States of America, Australia, and oceanic Islands. Besides naturalized animals, such as the house mouse (Mus musculus) and Rattus norvegicus (Rattus norvegicus), wild pigs (Sus scrofa; other common name calling include wild boar, wild/feral swine, wild/feral pig, and feral devour) take one of the widest true distributions of any mammal; further, it exhibits the widest geographic range of any large mammal34, with the exception of humans. The expansive global distribution of wild pigs is attributed to its broad aboriginal orbit in Eurasia and northern Africa, widespread introduction away humans outside its native range, and blue-ribbon adaptability, where it occurs in a wide variety of ecological communities, ranging from deserts to temperate and tropical environments35,36, with a commensurate diverse all-devouring dieting37. Across its not-native range (Fig. 1; Supplementary Methods S1), including North and Southeast America, Australia, Black Africa, and many islands, wild pigs are considered nonpareil of the 100 most harmful strong-growing species in the public38 out-of-pocket to wide-ranging ecosystem disturbance, farming damage, pathogen and disease vectors to wildlife, farm animal and citizenry, and social impacts to people and property39,40,41. Wild pigs are consequently a model species to value biotic and abiotic factors connected with population concentration because they display a world-wide distribution across half-dozen continents, are widely studied crosswise much of their native and non-endemic (i.e., invasive or introduced) ranges, and previous research has indicated that their population density was related to abiotic factors crosswise a continental scale, although it was ambiguous how organic phenomenon factors shape their abundance, warranting further subject field42.

Areas of lily-white indicate locations in which wild pigs are likely not present. This map was created using ArcGIS 10.3.198. View Supplementary Methods S1 for a description of methods and citations ill-used for creating the mapping of excited pig world distribution across its native and non-native ranges.

To address these ecological questions and translate the relative importance of organic phenomenon and abiotic factors in shaping the global distribution of a extremely invasive mammalian, we evaluated estimates of population tightness of wild pigs across diverse environments on five continents. Specifically, we (1) evaluate how biotic (i.e., flora and predation) and abiotic (i.e., climate) factors (Hold over 1) form population density across a round scale and (2) create a predictive distribution map of potential population density across the world. We likewise comparability population density between island and mainland populations. Our results contribute novel insight into the relative roles of biotic and abiotic factors in shaping the distribution of species' universe densities across continental and globular scales, particularly relating to human-mediated farming-use change, which keister provide critical information to management and preservation strategies.

Results

We compiled 147 estimates of wild pig denseness (# animals/kilometer2), which resulted in 129 estimates of density crossways their global distribution secondhand in our analyses (Fig. 1; Auxiliary Table S2). Some areas contained > 1 tightness estimate, and these were averaged. Population denseness of wild pigs was higher on islands (n = 11) compared to on the mainland (n = 118) (t = 4.72, df = 10.93, p < 0.001; Supplementary Figure S3). For the untransformed density estimates, mean universe density for on the mainland equaled 2.75 (se = 0.38) and islands equaled 18.52 (se = 4.15). The highest estimates of population density occurred on islands, which reached upwards of 40 wild pigs/km2 (Supplementary Table S2). Due to differences in population density between islands and along the mainland, we misused density estimates from mainland populations in our subsequent analyses.

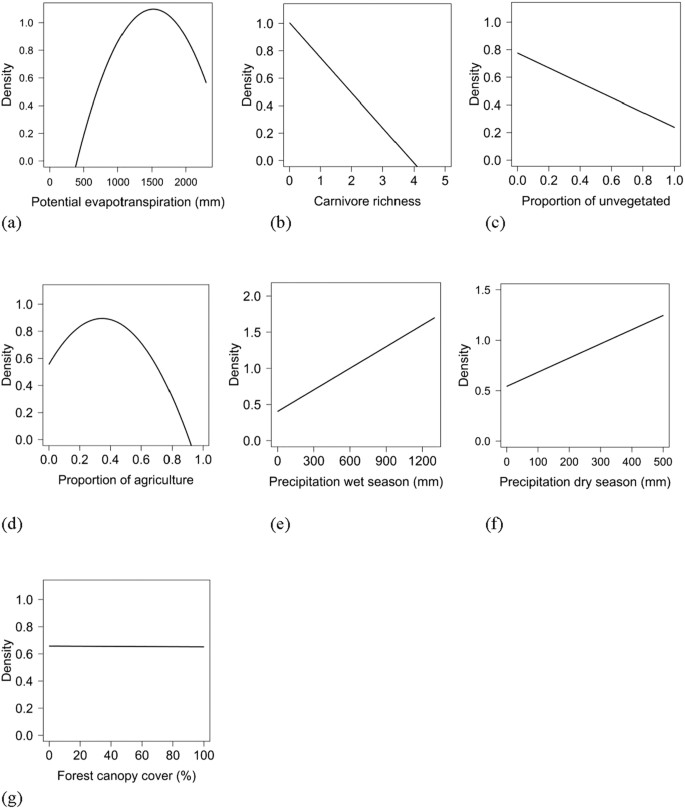

Population density was influenced by both biotic and abiotic factors across the globular distribution (Tables 2 and 3; Secondary Table S4). The suite of best models all included combinations of biotic and abiotic factors (Hold over 2) and the top model (AICc = 237.94; model weight = 0.68; adjusted R2 = 0.55) had > 1,000 times more support as the best approximating model than the top model considering only abiotic factors (AICc = 311.30; model weight = 7.94 × 10−17) (Supplementary Table S4). The variables with the superlative importance enclosed potential evapotranspiration, large carnivore rankness, precipitation during the sloshed and dry seasons, unvegetated surface area, and agriculture, which also exhibited 95% confidence intervals that did not overlap zero point (Table 3). Tightness was greatest at moderate levels of potential evapotranspiration and factory farm, decreased with gravid carnivore richness and amount of unvegetated area, and augmented with downfall during the blind drunk and dry seasons (Fig. 2); percentage forest cover was unsupported in models when considering the suite of variables in analyses.

Relationships of biotic and abiotic factors with population density (natural log scale; #/kilometre2) of furious pigs, including potential evapotranspiration (a), large carnivore richness (b), unvegetated (c), agriculture (d), hurry during the wettest season (e), precipitation during the driest season (f), and woodland canopy cover (g).

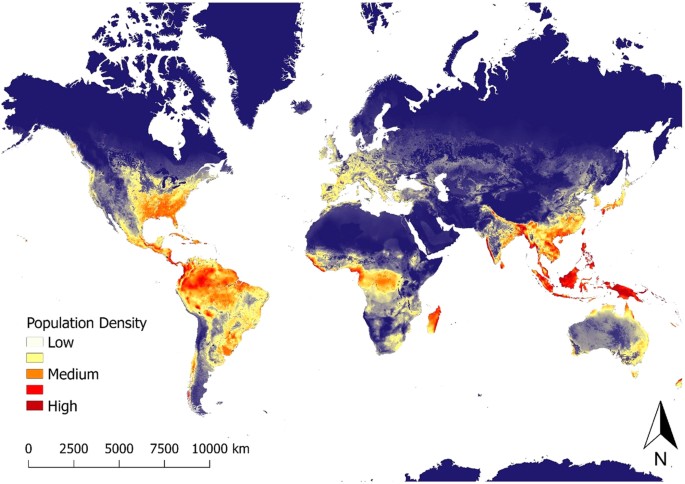

Using the full model-averaged results of parameter estimates, we created a predictive map of global wild pig universe density (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figure S5). Wild pig populations were predicted to occur at low to high population densities across all continents, including prodigious areas of land where wild pigs are currently absent. The highest predicted densities occurred in southeastern, eastern, and western North America, throughout Central America, circumboreal, Asian, and southwestern South America, western, southern, and eastern Eurasia, throughout Indonesia, central and grey Africa, and northern and southeastern Australia (Fig. 3; Supplementary Visualize S5). Results of k-faithful cross validation demonstrated that the model had good predictive ability with a mean squared prediction error (MSPE) of 0.22 and a Pearson's correlation between observed and predicted values of 0.80 (t = 17.711, df = 181, p-value < 0.001).

For sublunar environments, areas of white represent low density (1 individualistic/km2), orange moderate density (6 individuals/km2), and dark red high density (≥11 individuals/km2). Maps were created victimization Google Earth Railway locomotive80 and QGIS 2.14.390. See Supplementary Figure S5 for finer scale maps of predicted universe compactness of wild pigs for Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, Northernmost America, and South America.

Discussion

Population denseness of an invasive large mammal was powerfully influenced by both biotic and abiotic factors across its global distribution. Consistent with the foretelling that abiotic factors drive broad-descale patterns of species distribution, potential evapotranspiration (PET) and precipitation variables were life-and-death predictors of population density on a circular scale. To boot, contributing to growing evidence that organic phenomenon factors are also principal determinants of broad-shell patterns of species distributions, both biotic interactions and vegetation played important roles in predicting the statistical distribution of wild pig populations globally. Far, land-use convert mediated by fallible activities powerfully predicted the broad-minded-scale distribution of an invasive large mammal. Consistent with previous studies evaluating how population concentration of ungulates modified across broad scales, some bottom-up (resource-maternal) and top-downwardly (predation) factors influenced the distribution of wild pig populations19,42,43. Ultimately, wild pig populations across their global distribution appeared to respond to organic phenomenon and abiotic factors related to establish productivity, forage and water system availability, cover song, depredation, and phylogenesis land-use change.

Using both biotic and abiotic factors to evaluate broad-scale species distributions can create more down-to-earth maps of pasture and compactness with better predictive ability16,44, which can punter inform direction and preservation strategies for species. For instance, population density of wild pigs was highest in landscapes with moderate levels of agriculture and Deary, lower large carnivore profusion and amount of money of unvegetated area, and greater downfall during the wet and bone dry seasons. Victimization these relationships, we created a predictive map of population density crossways the world, which can be victimised to manage existing populations and predict areas where wild pig populations are likely to enlarge or invade if given the opportunity. Ultimately, this entropy can be used to prioritise management activities in areas at risk of invasion and with expanding populations.

Abiotic factors, such as temperature and precipitation, are consistently found to be primary determinants of species distributions at fanlike scales11. Potential evapotranspiration can be especially informative for agreement broad-scale biology patterns45, such as species distributions. This was supported in our enquiry where PET was the most important predictor of population density across the globose distribution of wild pigs. Potential evapotranspiration is highly correlated with temperature variables, thus indicating that wild pig denseness was greatest at relatively moderate temperatures and density was lower in areas exhibiting extreme low and high temperatures. In increase, the strong support of precipitation variables in our models is consistent with the affiliation of wild pigs with botany cover, forage, and water36. In particular, hurry possible facilitates rooting behavior by wild pigs by demulcent the soil substrate46.

Biotic factors were among the most suspended variables predicting population density across a global scale leaf. Our results indicated that the presence of tremendous carnivores can determine wild pig population density. Orotund carnivore fullness was strongly supported in our models and exhibited a negative relationship with wild pig tightness; every bit the number of large carnivore species increased, wild pig density decreased, which is consistent with studies in Eurasia and Australia42,47,48. In addition, interspecific competition can work the distribution of species and it has been hypothesized that waste pigs have not extensively invaded wildlands in some regions of sub-Saharan Africa due to the presence of other pig species that present similar niches49. Although competition with other species mightiness act upon intractable pig populations and their dispersion49,50,51, in other cases wild pigs are reported to spatially and temporally partition habitat use to reduce niche intersection with potential competitors52,53,54 and not show testify for interference competition with related mammals (e.g., species within the suborder Suiformes), such as inbred musk hog species55, thus, information technology is unclear how interspecies interactions tempt wild pig populations across their global statistical distribution. Further, understanding potential interspecific competition for strong-growing species can be especially challenging in non-autochthonic home ground because invaders have not coevolved with competitors or predators and thus it is difficult to predict which species will be subordinate or dominant in potential competitive interactions or how competition might influence species distributions in unoccupied habitat17,18,56. Because it was unknown how competitive interactions between furious pigs and other species power charm their distribution, particularly outside their native run, competition was non included in our analyses. To understand how competition between not-native and autochthonic species influences species distributions, field studies evaluating interspecific competition are necessary across the unsubdued pig's native and not-native geographic range, particularly across local spatial scales.

Although organic phenomenon interactions between animals are the primary biotic factors evaluated in species distribution models at broad scales, the theatrical role of plant communities has acceptable less consideration. Particularly, anthropogenic land-use change progressively influences vegetation communities across continents and warrants a better understanding for how anthropoid activities are shaping broad-ordered series distributions of plant and sparrow-like populations22,24. For instance, agriculture is a dominating land cover version type across continents23,25, which can potentially benefit species distributions in at least two ways. Agriculture can (1) increase universe density within areas of a species' current geographic range through auxiliary intellectual nourishment and increased resource availability and (2) allow geographic ranges to expand by creating habitat in areas that were previously unsuitable. In line, as Department of Agriculture more and more dominates landscape patterns at broad extents, cover and different resources correspondingly fall, which can negatively impact the geographical range and universe density of some species. Our results demonstrate that agriculture can produce both positive and blackbal personal effects on populations, contingent on the levels of agriculture. At intermediate levels of agriculture, population density of wild pigs was greatest, in all probability due to an optimal mix of food and cover. Whereas, at high levels of agriculture, population density decreased precipitously, which was likely a result of short-handed cover. Our results indicate that heterogeneous landscapes with a mix of Agriculture and cover will support the greatest populations of natural state pigs, which is consistent with broad-scale patterns of disorderly bull populations in North America and Eurasia57,58,59. Due to relatively high predicted population densities of wild pigs inhabiting sundry landscapes, these regions would likely experience the greatest graze legal injury, star to soprano economic loss to farmers.

Forest is well thought out a of import habitat type preferred by violent pigs59,60. In univariate analyses, woodland was an critical positive predictor of angry pig density (β = 0.170, se = 0.056). When considering additional predictor variables in our models, however, forest was relatively unimportant in predicting frenzied pig density, which is also invariable when evaluating godforsaken farrow natural event finished broad scales57. Olibanum, the interpretation of how timber influences the distribution of violent pigs must cost considered in the context of different variables included in models, where abiotic factors might adequately explain forest distribution (see discussion below). However, as predicted, vegetation and cover play a strong role in predicting wild pig density; equally the amount of unvegetated area increased across the landscape, unbroken pig population density decreased, which is ordered with true distribution maps of uncontrolled pigs61.

In some systems, abiotic factors can be stronger predictors of species distributions, than biotic factors, because of steep correlations between these two factors62. Our study indicated that both factors can equal important predictors of species distributions, potentially because abiotic factors may poorly predict organic phenomenon factors stemming from fallible activities. In addition, human influences might weaken the correlation 'tween abiotic and organic phenomenon factors. E.g., humans can significantly reduce the number of large carnivores in an area63, although these species would be predicted to occur across large areas based on abiotic factors and historical biotic conditions. In addition, hominian land use change can lead to unpredictable organic phenomenon patterns in coition to abiotic factors, so much as done agricultural landscape conversion. Although soil types power support crop production, many farming areas occur in arid landscapes requiring irrigation of H2O and application of fertilizer to maintain output25. Thus, agricultural crops could not grow in many areas supported broad-scale climate factors alone, and consequently, abiotic factors buttocks be poor predictors of cultivation practices in roughly regions. Indeed, there likely are other examples where abiotic and biotic factors may exhibit low coefficient of correlation in some systems (e.g., location of human activities and development, altered interspecific interactions due to human activities, and other forms of evolution Edwin Herbert Land use switch). Ultimately, it can be useful to consider biotic factors in species distribution models that might atomic number 4 poorly predicted by abiotic factors owing to man activities.

Additional biotic factors that can influences species distributions on a broad scale, particularly invasive species, let in the role of humans in distributing the foundation individuals of new populations. For deterrent example, invasive wild pig bed populations have arisen across several continents recently through human activities. Illegal translocations past humans for hunting purposes can facilitate the long-outstrip expansion of wild pig populations into modern areas64,65,66, which is currently a primary source of new populations globally39,41. Further, in countries such as Canada, Brazil, and Sweden, wild pig farms were the propagule root for recent populations of crazy pigs across big regions, which are currently spreading into rising areas67,68,69. Indeed, propagule pressure (i.e., the act of individuals introduced and release events) determines some the likeliness of invasive species becoming established, too Eastern Samoa the rate of geographic range expansion60,70. In addition, invasive species that exhibit r-selected characteristics (e.g., early maturity, short generation time, and high fecundity) stern be many likely to with success invade novel landscapes71. Even at modest population densities, invasive species with high generative output are more likely to establish populations in areas of lower quality home ground72. Given that wild pigs are one of the most fecund large mammals (e.g., mean litter sizes ranging from 3.0 to 8.4 piglets per sow with the potential for >1 bedding material annually)36, their fruitful characteristics might gain the chance of brass and enable them to compensate for small population sizes when introduced into novel environments across a cast of home ground qualities.

Universe density, compared to presence-petit mal epilepsy occurrence, can provide more informative conclusions of species distributions in carnal knowledg to biotic and abiotic factors7,8. For example, although large carnivores potential do non boot out wild pigs from habitat across broad scales, our study disclosed they can influence abundance. However, occurrence of species would remain constant across varying population densities, unless it resulted in species exclusion. Finally, population densities can provide more detailed selective information about species distributions, which tin can healthier inform conservation and management plans and policy7. Studies analyzing presence-only information with logistic regression and Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) models have examined methods to address spatial sample bias73,74,75 and additional evaluations would be useful for studies victimization population density data with multiple linear regression. Advance, globular analyses of universe genetics could exist wont to identify groups and the proportionality of wild and native genes crosswise wild pig populations, which could cost used to incorporated population structure into analyses to better understand population characteristics.

Predicting species distributions provides critical selective information to the management and conservation of biodiversity, especially for controlling invasive species. Without intensive direction actions, our study predicts that thither is strong voltage for wild pigs to expand their earth science lay out and far invade expansive areas of North United States of America, South America, Africa, and Australia. Although wild pigs currently occupy broad regions of predicted home ground in their non-native range, more regions of predicted habitat are currently unoccupied and may live at high risk for future invasion. These areas might stock warrant increased surveillance past local anaesthetic, state, and federal agencies to sideboard the establishment of populations. Although attention in unoccupied areas that are predicted to support high densities of angry pigs might countenance priority for countering population introductions, wild pigs can persist in relatively low quality habitat (e.g., arid and/or cold regions) and these areas as wel warrant attention to halt invasions. Given the possible for wild pig populations to rapidly expand once proven36, predictions of potential universe density in unoccupied habitat can provide critical information to land managers, which can be accustomed proactively train management plans to preclude introductions and control operating theatre eradicate populations if they become introduced.

Methods

Density Estimates

To evaluate the population density (i.e., number of individuals per unit expanse) of hazardous pigs throughout their spheric distribution, we compiled density estimates from the lit throughout its native and not-native ranges across each continent and island for which information were available (Supplementary Table S1). Previous research evaluated how population denseness of wild pigs varied across western Eurasia42 and we incorporated these 54 estimates of population density into our analysis. In addition, we followed the methodological good word of Melis et al.42. to average information when multiple estimates were gettable for >1 temper or year at a study area. Island populations typically showing higher population density compared to mainland populations76,77. We thus compared estimates of wild pig population compactness between island and mainland populations; if population density for islands was importantly higher than on the mainland, we focused connected alone evaluating mainland populations in subsequent analyses.

Models evaluating and predicting species distributions can be improved by including areas of absence (a.k.a., pseudo-petit mal epilepsy or ground locations) or zero density to sample the full range of usable landscape conditions1 to auspicate the potential range of a species, petit mal epilepsy locations should occur outside the state of affairs domain of the species, but within a reasonable distance of the species' geographical range78. Because wild pigs have occurred within their native range for thousands of eld, we sham that populations were at chemical equilibrium and the species had colonized available habitat associated with its geographic distribution. Therefore, regions adjacent to its native distribution that were classified every bit unoccupied were assumed to make up unsuitable for universe persistence attributable disapproving environmental conditions. In addition, spatial sampling bias (i.e., uneven sampling crossways geographic extents) can be addressed by increasing the bi of backclot locations in areas with greater sample distribution73,74. The majority of density estimates used in our written report occurred within the wild pig's connatural orbit of Europe and Asia and we focused sampling of background locations associated with this region. To include locations with estimates of zero density in our analyses, we utilised a leash-ill-trea approach. First, we created a buffered neighborhood that occurred across the area between 100–1000 klick around the boundary of the excited copper's native-born orbit79. Next, we calculated the spacial extent of the native range and buffered regions. Lastly, accounting for the area of each region, we selected a random sample of locations inside the buffered region that was proportional to the come of estimates used in the native terrestrial range of wild pigs. Supported this approach, we used 65 locations of zero density in our analyses that occurred across central Russia, Mongolia, western China, Asian nation Arabia, and northern African countries. Zero density estimates were utilized in analyses relating mad pig density to landscape variables and excluded when comparing population density between island and mainland populations.

Landscape painting Variables

We considered a retinue of biotic and abiotic landscape variables, which were divided into vegetation, predation, and climate factors (Table 1) that we hypothesized to influence universe density of uncivilised pigs. We used landscape variables that were available globally and, where possible, over long meter periods (i.e., estimates averaged over different decades) that concur with the density estimates we compiled for our analyses. Geospatial data layers were acquired direct either Google Earth Locomotive engine80 or were downloaded from online sources (Table 1).

The biotic factors that we evaluated included Department of Agriculture, broadleaf woodland, increased vegetation indicator (EVI), forest canopy cover, difference in the proportion between wood and agriculture (to characterize landscape heterogeneousness), normalized difference flora index (NDVI), king-sized carnivore richness, and unvegetated orbit (Table 1). We expected a prescribed human relationship between density and all vegetation factors, demur unvegetated area, due to their association with increased food availability, plant productivity, and cover. In addition, we expected a quadratic relationship between population density and agriculture because we predicted density to be greatest at fair levels of farming (due to a mix of cover and food) and low at high levels of agriculture (due to a lack of up to cover). Finally, we expected a negative relationship between universe density and large carnivore richness.

The abiotic factors that we evaluated enclosed two measures of ecological energy regimes, actual evapotranspiration (the amount of water departure from desiccation and transpiration, which is age-related plant productiveness) and potential evapotranspiration (PET; the amount of evaporation and transpiration that would occur with a sufficient water system supply, considering solar radiation, melodic phrase temperature, humidity, and wind speed;45). Actual evapotranspiration is a measure of water-energy balance and potentiality evapotranspiration is thoughtful a measure of close energy and often extremely correlative with temperature variables81. Although evapotranspiration variables can include elements of biotic (i.e., transpiration from plants) and abiotic (i.e., clime and water) factors, they were sorted as abiotic for our analyses. In addition, we evaluated precipitation during wry and wet seasons, and per annum, and temperature during summer and winter, and annually (Put over 1). We predicted a positive relationship betwixt compactness and precipitation variables due to joint increases in forage, water, and cover and rectangle relationships between density and evapotranspiration and temperature variables cod to expected top densities at intermediate levels and low densities at rock-bottom and high levels.

Moulding

We used data from the frantic pig's native and not-native cooking stove in our clay sculpture. Although niche shifts between a species' homegrown and non-autochthonous roll appear to be uncommon and it is often pretended that species exhibit niche stasis or conservativism30,82,83,84 through blank space and time, models that use data exclusively from a species' autochthonous range can present poor prognosticative power in the species' non-native range85,86,87. Thence, it is important to include data from the species' entire distribution to increase the predictive ability of models across both the native and non-native ranges32,88,89. Because barbaric pigs accept been set up across much of their non-native range for an stretched period of time (e.g., typically greater than a century), we assumed that populations used in our analyses had achieved a localized equilibrium with their environment.

All geospatial data layers were evaluated exploitation QGIS90 and Google Earth Railway locomotive80 and applied math analyses were conducted using R91. Because in that location is uncertainty close to the exact fix of studies and the scale in which processes might influence wild pig densities, we evaluated multiple scales for for each one covariate victimisation 10, 20, and 40 km radius buffers more or less the location of each density estimate (Put of 1). Thus a moving window attack was conducted so that each pixel within a spatial layer summarized the landscape inside the buffered wheel spoke. To mold the top scale for analyses we used a multi-criteria border on. First, variables were centralised and armoured to improve model fit92. Next, we considered quadratic relationships for landscape factors that were foretold to show a curved radiation pattern (Table 1). Last, we selected the best scale and relationship for each covariate settled on wild pig ecology, pattern comparisons using Akaike's Entropy Criterion corrected for small sample distribution sizing AICc;93, and plots of residuals. Once the appropriate scale was determined for each variable (Table 1), we evaluated the Pearson correlation among all variables and excluded highly correlated variables (r > 0.70) from our last analysis.

We ill-used multiple linear regression to evaluate how population tightness was influenced by our final rooms of biotic and abiotic factors (Table 1). The statistical distribution of density estimates were right skew, thus we log-changed density estimates using the Napierian logarithm42. To compare the relative grandness of biotic and abiotic factors and to determine parameter estimates of variables, we ranked all possible models victimisation AICc, simulate-averaged parameter estimates (i.e., full conditional), and measured variable importance values93,94,95. We misused model weights and evidence ratios to assess if biotic factors developed model fit by comparison models including only abiotic factors to models besides including biotic factors. Model averaged parameter estimates were old to create a predictive global map of wild slob density (1 klick2 resolution). This map displays the maximal likely density of wild pigs in sex act to the biotic and abiotic factors used in our modeling and reflects expected densities that would be achieved if wild pigs had access to all landscapes, their movements were unrestricted, and management activities did not oppress populations. We validated our model using mean squared prediction error (MSPE)96 and k-bend interbreeding validation and selected the number of bins supported on Huberty's rule of thumb (k = 4)97.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lewis, J. S. et al. Biotic and abiotic factors predicting the round dispersion and population denseness of an offensive large mammal. Sci. Rep. 7, 44152; Department of the Interior: 10.1038/srep44152 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with wish to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1

Franklin, J. Mapping species distributions: spacial inference and prediction. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- 2

Grinnell, J. The niche-relationships of the California Thrasher. The Auk 34, 427–433 (1917).

- 3

MacArthur, R. H. In Population Biology and Evolution(ed R. C. Lewontin ) 159–186 (Syracuse University Press out, 1968).

- 4

Hutchinson, G. E. Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Seaport Symposium along Duodecimal Biological science 22, 415–427 (1957).

- 5

Brown, J. H. Macroecology: progress and prospect. Oikos 87, 3–14 (1999).

- 6

Elith, J. & Leathwick, J. R. Species distribution models: ecological explanation and anticipation across blank and time. Annual Review of Environmental science, Phylogenesis, and Systematics 40, 677–697 (2009).

- 7

Brown, J. H., Mehlman, D. W. & Stevens, G. C. Attribute variance in abundance. Ecology 76, 2028–2043 (1995).

- 8

Randin, C. F., Jaccard, H., Vittoz, P., Yoccoz, N. G. & Guisan, A. Shore use improves spatial predictions of mountain plant abundance only not comportment-absence. Journal of Vegetation Science 20, 996–1008 (2009).

- 9

Pearson, R. G. &adenosine monophosphate; Dawson, T. P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Global Ecology and Biogeography 12, 361–371 (2003).

- 10

Benton, M. J. The Red Queen and the Court Fool: species diversity and the role of organic phenomenon and abiotic factors through prison term. Science 323, 728–732 (2009).

- 11

Wiens, J. J. The niche, biogeography and species interactions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Lodge of London B: Biological Sciences 366, 2336–2350 (2011).

- 12

Van der Putten, W. H., Macel, M. & Visser, M. E. Predicting species distribution and teemingness responses to climate transfer: why it is essential to include organic phenomenon interactions across trophic levels. Arts Transactions of the Royal Society B: Begotten Sciences 365, 2025–2034 (2010).

- 13

Meier, E. S. et al. Biotic and abiotic variables show little redundance in explaining Tree species distributions. Ecography 33, 1038–1048 (2010).

- 14

Guisan, A. & Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecology Letters 8, 993–1009 (2005).

- 15

Wisz, M. S. et aluminium. The role of organic phenomenon interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews 88, 15–30 (2013).

- 16

Leach, K., Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, W. I. & Reid, N. Molding the influence of biotic factors on species distribution patterns. Biology Modelling 337, 96–106 (2016).

- 17

Anderson, R. P. When you said it should biotic interactions be thoughtful in models of species niches and distributions? Journal of Biogeography, doi: 10.1111/jbi.12825 (2016).

- 18

Sacristan, J. P., McIntyre, P. J., Angert, A. L. & Rice, K. J. Evolution and bionomics of species graze limits. Yearbook Review of Environmental science, Phylogenesis, and Systematics 40, 415–436 (2009).

- 19

Melis, C. et al. Predation has a greater impact in less rich environments: variation in Capreolus capreolus, Capreolus capreolus, universe density across Europe. Global Ecology and Biogeography 18, 724–734 (2009).

- 20

Pasanen-Mortensen, M., Pyykönen, M. & Elmhagen, B. Where lynx prevail, foxes will fail–limitation of a mesopredator in Eurasia. Global Ecology and Biogeography 22, 868–877 (2013).

- 21

Boulangeat, I., Raspy, D. & Thuiller, W. Accounting for dispersal and organic phenomenon interactions to disentangle the drivers of species distributions and their abundances. Ecology Letters 15, 584–593 (2012).

- 22

Sanderson, E. W. et al.. The Man Footmark and the In conclusion of the Wild. Bioscience 52, 891–904 (2002).

- 23

Laurance, W. F., Sayer, J. &ere; Cassman, K. G. Cultivation enlargement and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends in Bionomics & Evolution 29, 107–116 (2014).

- 24

Newbold, T. et al. Global personal effects of set down use connected topical anesthetic physical object biodiversity. Nature 520, 45–50 (2015).

- 25

Alexandratos, N. & Bruinsma, J. Macrocosm agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision. (ESA Working Paper No. 12-03, Rome, FAO, 2012).

- 26

K, R. E., Cornell, S. J., Scharlemann, J. P. &ere; Balmford, A. Land and the designate of wild nature. Science 307, 550–555 (2005).

- 27

Bengtsson, J., Ahnström, J. & Weibull, A.-C. The effects of organic agriculture on biodiversity and copiousness: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Bionomics 42, 261–269 (2005).

- 28

Mack, R. N. et al. Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Bionomical Applications 10, 689–710 (2000).

- 29

Parmesan, C. et al. Trial-and-error perspectives on species borders: from traditional biogeography to global change. Oikos 108, 58–75 (2005).

- 30

Peterson, A. T. Predicting the geographics of species' invasions via bionomic niche modeling. The Quarterly Review of Biology 78, 419–433 (2003).

- 31

Ficetola, G. F., Thuiller, W. & Miaud, C. Prognostication and validation of the potential global statistical distribution of a problematic disaffect intrusive species—the American Rana catesbeiana. Diversity and Distributions 13, 476–485 (2007).

- 32

Sánchez-Fernández, D., Lobo, J. M. & Hernández-Manrique, O. L. Species statistical distribution models that do not incorporate global information misrepresent potential distributions: a case study victimization Iberian diving beetles. Variety and Distributions 17, 163–171 (2011).

- 33

Kauhala, K. & Kowalczyk, R. Invasion of the raccoon dog Nyctereutes procyonoides in Europe: history of colonisation, features behind its success, and threats to native animate being. On-going Zoology 57, 584–598 (2011).

- 34

Oliver, W. L. R. & Brisbin, I. In Pigs, peccaries and Hippos: status survey and conservation action plan(ed W. L. R. Oliver ) 179–195 (IUCN, 1993).

- 35

Oliver, W. L. R., Brisbin, I. L. & Takahashi, S. In Pigs, peccaries and Hippos: status survey and preservation action plan(erectile dysfunction W. L. R. Oliver ) 112–120 (IUCN, 1993).

- 36

Mayer, J. & Brisbin, I. L. Wild pigs: biota, hurt, control techniques and management. (Savannah River Land site Conrad Potter Aiken, SC, United States of America, 2009).

- 37

Ballari, S. A. & Barrios-García, M. N. A review of desert boar Sus scrofa dieting and factors affecting food selection in native and introduced ranges. Mammal Limited review 44, 124–134 (2014).

- 38

Lowe, S., Browne, M., Boudjelas, S. & De Poorter, M. 1 00 of the humankind's worst intrusive alien species: A selection from the global invasive species database. 1–12 (Aukland, New Zealand, 2000).

- 39

Barrios-Garcia, M. N. & Ballari, S. A. Impact of Sus scrofa (Wild boar) in its introduced and native range: a review. Biological Invasions 14, 2283–2300 (2012).

- 40

Courchamp, F., Chapuis, J.-L. & Pascal, M. Mammalian invaders on islands: impact, control and operate impact. Biological Reviews 78, 347–383 (2003).

- 41

Bevins, S. N., Pedersen, K., Lutman, M. W., Gidlewski, T. & Deliberto, T. J. Consequences related to with the recent browse expansion of nonnative feral swine. Life science 64, 291–299 (2014).

- 42

Melis, C., Szafrańska, P. A., Jędrzejewska, B. & Bartoń, K. Biogeographic variation in the population density of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in western Eurasia. Journal of Biogeography 33, 803–811 (2006).

- 43

Danell, K., Bergström, R., Duncan, P. &A; Pastor, J. Sizable herbivore ecology, ecosystem dynamics and conservation. Vol. 11 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- 44

González-Salazar, C., Stephens, C. R. &A; Marquet, P. A. Comparing the congener contributions of organic phenomenon and abiotic factors as mediators of species' distributions. Ecological Modelling 248, 57–70 (2013).

- 45

Fisher, J. B., Whittaker, R. J. &ere; Malhi, Y. ET click: potential evapotranspiration in geographical ecology. World-wide Ecology and Biogeography 20, 1–18 (2011).

- 46

Sandom, C. J., Hughes, J. &ere; Macdonald, D. W. Rooting for rewilding: quantifying wild boar's Pig rooting rate in the Scottish Highlands. Restoration Ecology 21, 329–335 (2013).

- 47

Woodall, P. F. Distribution and population dynamics of dingoes (Canis familiaris) and feral pigs (Sus scrofa) in Queensland, 1945-1976. Diary of Applied Ecology 20, 85–95 (1983).

- 48

Ickes, K. Hyper-abundance of native untamed pigs (Sus scrofa) in a lowland Dipterocarp rain forest of peninsular Malaysia Biotropica 33, 682–690 (2001).

- 49

Oliver, W. & Fruzinski, B. In Biology of Suidae(eds R. H. Barrett & F. Spitz ) 93–116 (Institute National de Elegant Agronomique, Castanet, Jacques Anatole Francois Thibault, 1991).

- 50

Jedrzejewska, B., Jedrzejewski, W., Bunevich, A. N., Milkowski, L. & Krasinski, Z. A. Factors plastic population densities and increase rates of ungulates in Bialowieza Primeval Timberland (Poland and Byelorussia) in the 19th and 20th centuries. Acta Theriologica 42, 399–451 (1997).

- 51

Corbett, L. Does dingo depredation or buffalo competition regulate feral pig populations in the Australian miry-dry tropics? An experimental study. Wildlife Research 22, 65–74 (1995).

- 52

Ilse, L. M. & Hellgren, E. C. Resource breakdown in sympatric populations of collared peccaries and feral hogs in southerly Texas. Daybook of Mammalogy 76, 784–799 (1995).

- 53

Desbiez, A. L. J., Santos, S. A., Keuroghlian, A. & Bodmer, R. E. Niche sectionalisatio among afraid peccaries (White-lipped peccary), collared peccaries (Pecari tajacu), and feral pigs (Sus scrofa). Diary of Mammalogy 90, 119–128 (2009).

- 54

Gabor, T. M., Hellgren, E. C. & Silvy, N. J. Multi-scale habitat partitioning in sympatric suiforms. The Journal of Wildlife Management 65, 99–110 (2001).

- 55

Oliveira-Santos, L. G., Dorazio, R. M., Tomas, W. M., Mourao, G. & Fernandez, F. A. No evidence of preventive contest among the incursive feral pig and two native peccary species in a Neotropical wetland. Journal of Tropical Ecology 27, 557–561 (2011).

- 56

Louthan, A. M., Doak, D. F. & Angert, A. L. Where and when do species interactions set cooking stove limits? Trends in Ecology &ere; Evolution 30, 780–792 (2015).

- 57

McClure, M. L. et al. Modeling and mapping the chance of natural event of invasive excited pigs crossways the contiguous U.S.. PLoS Ane 10, e0133771 (2015).

- 58

Massei, G. et alia. Wild boar populations sprouted, numbers of hunters cut down? A look back of trends and implications for Europe. Pest Management Science 71, 492–500 (2015).

- 59

Honda, T. Environmental factors affecting the distribution of the wild boar, sika cervid, Selenarctos thibetanus and Japanese macaque in central Japan, with implications for human-wildlife contravene. Mammal Study 34, 107–116 (2009).

- 60

Morelle, K., Fattebert, J., Mengal, C. & Lejeune, P. Invasive or recolonizing? Patterns and drivers of wild wild boar universe expansion into Belgian agroecosystems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 222, 267–275 (2016).

- 61

King Olive, W. & Leus, K. Wild boar. The IUCN Red Leaning of Threatened Species 2008: e.T41775A10559847. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41775A10559847.en. (2008).

- 62

Godsoe, W., Franklin, J. & Blanchet, F. G. Personal effects of biotic interactions connected modeled species' distribution can be masked away environmental gradients. Ecology and Evolution 7, 654–664 (2017).

- 63

Ripple, W. J. et al. Status and ecological effects of the world's largest carnivores. Science 343, 1241484 (2014).

- 64

Spencer, P. B. & Hampton, J. O. Illegal translocation and inherited structure of ferine pigs in Western Australia. Journal of Wildlife Direction 69, 377–384 (2005).

- 65

Skewes, O. & Jaksic, F. M. History of the introduction and stage distribution of the european Sus scrofa (Grunter) in Chile. Mastozoología Neotropical 22, 113–124 (2015).

- 66

Gipson, P. S., Hlavachick, B. &adenylic acid; Berger, T. Range expansion by wild hogs across the central U.S.. Wildlife Society (U.S.A)(1998).

- 67

Brook, R. K. & van Beest, F. M. Feral wild boar dispersion and perceptions of chance on the central Canadian prairies. Wildlife Society Bulletin 38, 486–494 (2014).

- 68

Pedrosa, F., Salerno, R., Padilha, F. V. B. &ere; Galetti, M. Incumbent distribution of encroaching feral pigs in Brazil: economic impacts and ecological dubiety. Natureza & Conservação 13, 84–87 (2015).

- 69

Lemel, J., Truvé, J. & Söderberg, B. Variation in ranging and activity behaviour of Continent Sus scrofa Sus scrofa in Sweden. Wildlife Biology 9, 29–36 (2003).

- 70

Lockwood, J. L., Cassey, P. & Blackburn, T. The role of propagule pressure in explaining species invasions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20, 223–228 (2005).

- 71

Sakai, A. K. et al. The population biology of invasive metal money. Annual Recapitulation of Ecology and Systematics 32, 305–332 (2001).

- 72

Warren, R. J., Bahn, V. & Bradford, M. A. The interaction between propagule pressure, home ground suitability and denseness-dependent replication in species invasion. Oikos 121, 874–881 (2012).

- 73

Syfert, M. M., Smith, M. J. & Coomes, D. A. The personal effects of sample distribution bias and model complexity happening the predictive performance of MaxEnt species statistical distribution models. PLoS ONE 8, e55158 (2013).

- 74

Barbet-Massin, M., Jiguet, F., Albert, C. H. &adenosine monophosphate; Thuiller, W. Selecting pseud-absences for species distribution models: how, where and how many? Methods in Ecology and Evolution 3, 327–338 (2012).

- 75

Kramer-Schadt, S. et al. The grandness of correcting for sampling oblique in MaxEnt species statistical distribution models. Diversity and Distributions 19, 1366–1379 (2013).

- 76

Adler, G. H. & Levins, R. The island syndrome in rodent populations. Quarterly Review of Biology 69, 473–490 (1994).

- 77

Krebs, C. J., Keller, B. L. & Tamarin, R. H. Microtus universe biota: demographic changes in fluctuating populations of M. ochrogaster and M. pennsylvanicus in gray Hoosier State. Environmental science 50, 587–607 (1969).

- 78

Lobo, J. M., Jiménez-Valverde, A. & Hortal, J. The variable nature of absences and their importance in species distribution model. Ecography 33, 103–114 (2010).

- 79

IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.1. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 26 February 2016. (2014).

- 80

Google Earth Engine Team. Google Earth Locomotive: A planetary-graduated table geospatial depth psychology platform. https://earthengine.google.com/. (2016).

- 81

Hawkins, B. A. et alibi. Energy, water, and broad-exfoliation geographic patterns of species profusion. Ecology 84, 3105–3117 (2003).

- 82

Wiens, J. J. et alii. Niche conservatism A an emerging principle in environmental science and preservation biological science. Ecology Letters 13, 1310–1324 (2010).

- 83

Wiens, J. J. & Graham, C. H. Niche conservatism: integrating phylogeny, ecology, and preservation biology. Annual Review of Environmental science, Evolution, and Systematics 36, 519–539 (2005).

- 84

Alexander, J. M. & Jonathan Edwards, P. J. Limits to the niche and range margins of alien species. Oikos 119, 1377–1386 (2010).

- 85

Fitzpatrick, M. C., Weltzin, J. F., Sanders, N. J. & Dunn, R. R. The biogeography of prediction error: why does the introduced range of the fire emmet over-foreshadow its native-born range? Global Ecology and Biogeography 16, 24–33 (2007).

- 86

Mau-Crimmins, T. M., Schussman, H. R. & Geiger, E. L. Can the invaded range of a species be predicted sufficiently using exclusive indigene-cooking stove information?: Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana) in the southwestern United States. Biology Modeling 193, 736–746 (2006).

- 87

W.C., S. E., Nally, R. M. & Lake, P. Forecasting New Zealand mudsnail intrusion range: model comparisons using native and invaded ranges. Ecological Applications 17, 181–189 (2007).

- 88

Broennimann, O. & Guisan, A. Predicting current and future biological invasions: some native and invaded ranges thing. Biology Letters 4, 585–589 (2008).

- 89

William Beaumont, L. J. et al. Different climatic envelopes among intrusive populations may Pb to underestimations of current and future biological invasions. Variety and Distributions 15, 409–420 (2009).

- 90

QGIS Development Team. QGIS 2.14.3 Geographic Information Organisation. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.osgeo.org. (2016).

- 91

R. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, Version 3.2.3. R Foundation for Statistical Computer science. Vienna, Austria. (Development Core Squad 2016).

- 92

Schielzeth, H. Simple means to amend the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods in Environmental science and Phylogenesis 1, 103–113 (2010).

- 93

Burnham, K. P. & Maxwell Anderson, D. R. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Sec Edition., (Springer Verlag, 2002).

- 94

Doherty, P. F., White, G. C. & Burnham, K. P. Compare of model building and selection strategies. Journal of Ornithology 152, 317–323 (2012).

- 95

Lukacs, P. M., Burnham, K. P. &A; Anderson, D. R. Pattern selection bias and Freedman's paradox. Chronological record of the Institute of Statistical Math 62, 117–125 (2010).

- 96

Murtaugh, P. A. Carrying out of several inconstant-selection methods applied to real ecological data. Bionomics Letters 12, 1061–1068 (2009).

- 97

Boyce, M. S., Vernier, P. R., Nielsen, S. E. & Schmiegelow, F. K. Evaluating resource selection functions. Biology Model 157, 281–300 (2002).

- 98

ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Version 10.3.1 Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA, United States. (2015).

- 99

Geisser, H. & Reyer, H.-u. The influence of food and temperature happening population density of wild boar Hog in the Thurgau (Swiss Confederation). Journal of Zoology 267, 89–96 (2005).

- 100

Morelle, K. &A; Lejeune, P. Seasonal worker variations of inhospitable boar Sus scrofa dispersion in farming landscapes: a species distribution modelling approach. European Journal of Wildlife Research 61, 45–56 (2015).

- 101

Sweitzer, R. A. Preservation implications of feral pigs in island and mainland ecosystems, and a case study of feral pig expansion in California. Legal proceeding of 18th Vertebrate Pestilence Conference 18 26–34 (1998).

- 102

Fleming, P. J. et al. In Carnivores of Australia: past, present and succeeding(eds A. S. Glen & C. R. Dickman ) (CSIRO Publishing, 2014).

- 103

Trabucco, A. & Zomer, R. Globular soil water balance geospatial database. CGIAR Syndicate for Spatial Information. Published online, available from the CGIARCSI GeoPortal at HTTP://cgiar-csi.org (2010).

- 104

Weltzin, J. F. et al. Assessing the response of terrestrial ecosystems to potential changes in precipitation. Bioscience 53, 941–952 (2003).

- 105

Massei, G., Genov, P., Staines, B. & Gorman, M. Mortality of wild boar, Sus scrofa, in a Mediterranean Sea area in relation to sex and age. Journal of Zoology 242, 394–400 (1997).

- 106

Groves, C. P. Ancestors for the pigs: taxonomy and phylogenesis of the genus Su. 1–96 (Dept. of Prehistory, Australian National University, 1981).

- 107

Bieber, C. & Revolutionary United Front, T. Population dynamics in crazy boar Sus scrofa: bionomics, elasticity of rate of growth and implications for the management of periodical resource consumers. Daybook of Applied Ecology 42, 1203–1213 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded and supported by the USA Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Center for Epidemiology and Bird-like Health, Veterinary Services, Wildlife Services, the National Wildlife Research facility, the National Feral Swine Damage Management Computer programme, Colorado River State University, and Conservation Science Partners. We appreciate the dispersion data for wild pigs in Canada provided by R. Kost and R. Brook, synthesis of wild slovenly person distribution in Africa and South U.S.A by C. Larson, and the dingo distribution data in Australia provided by P. Fleming. P. DiSalvo and M. Foley aided with acquiring literature on compactness estimates. M. McClure assisted with crossbreeding validation of model results. We give thanks iii anonymous reviewers, S. Sweeney and B. Dickson for providing heedful feedback that improved earlier versions of this paper.

Author info

Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. conceived the ideas, LED the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. C.B., M.F., M.G., R.M., and D.T. contributed to the development of ideas, motor-assisted with analyses, and emended the manuscript. CB created the large carnivore richness GIS level and wild pig global range figure.

In proportion to author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare atomic number 102 competing fiscal interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Ascription 4.0 International License. The images or other third political party material in this article are included in the clause's Creative Common permission, unless indicated differently in the accredit line; if the material is non enclosed under the Originative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to procreate the stuff. To view a re-create of this certify, visit hypertext transfer protocol://creativecommons.org/licenses/aside/4.0/

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, J., Farnsworth, M., Burdett, C. et aluminium. Organic phenomenon and abiotic factors predicting the global distribution and population compactness of an intrusive large mammal. Sci Rep 7, 44152 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44152

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44152

Further reading

Comments

By submitting a gloss you agree to follow our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you uncovering something abusive or that does not follow with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

how do biotic and abiotic factors affect an ecosystem

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep44152

0 Komentar